The question of what philosophy is always made me squirm. People would ask me what I do, I’d tell them, and then they would ask me what it exactly was that I do. But now I have a answer.

A while back I heard a quote attributed to Russell that went roughly:

Philosophy starts out with propositions that everyone would accept as true, and then ends up with propositions that no one would accept as true.

I thought this made philosophers sound like jerks, but there was something to it: we do end up in weird places for some reason. Here’s why:

Writing philosophy is like writing an instruction manual. You have some act or object or situation that you want to explain because it is hard to use or complicated or dangerous for some reason. So you set out to make a manual for the thing, starting from the most obvious and basic features. Now if you don’t know the thing perfectly, in and out, you end up having bad instructions, regardless of where you started. Then when you try to do something, or understand your object, when you follow the instructions you become hopelessly lost. Both your instructions and whatever the instructions were for are completely inscrutable. But if the instructions are good, then you can do things that were impossible for you to do before hand (program you VCR (or DVR), explain why mathematics is incomplete, that sort of thing). Philosophy is an attempt at writing instruction manuals for confusing things.

This answers the ontological questions of

- Whether or not philosophy is true: it is true if it accurately describes the phenomenon it is attempting to explain. However, since many times we are in the position of not knowing the phenomenon in question, philosophy is often of indeterminate truth.

- Why philosophy is inherently obscure: who ever reads the manual? (I do by the way)

- How best to characterize the strange layouts of philosophical treatises, a la manuals: the beginning is packed with warnings about what is wrong and and dangerous, then basic, most common functions are listed and the interesting and difficult features are buried in jargon somewhere towards the end.

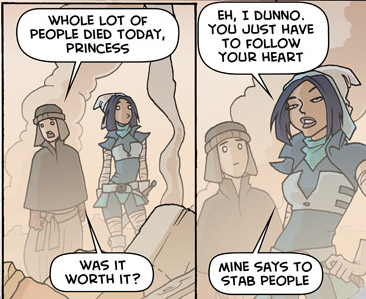

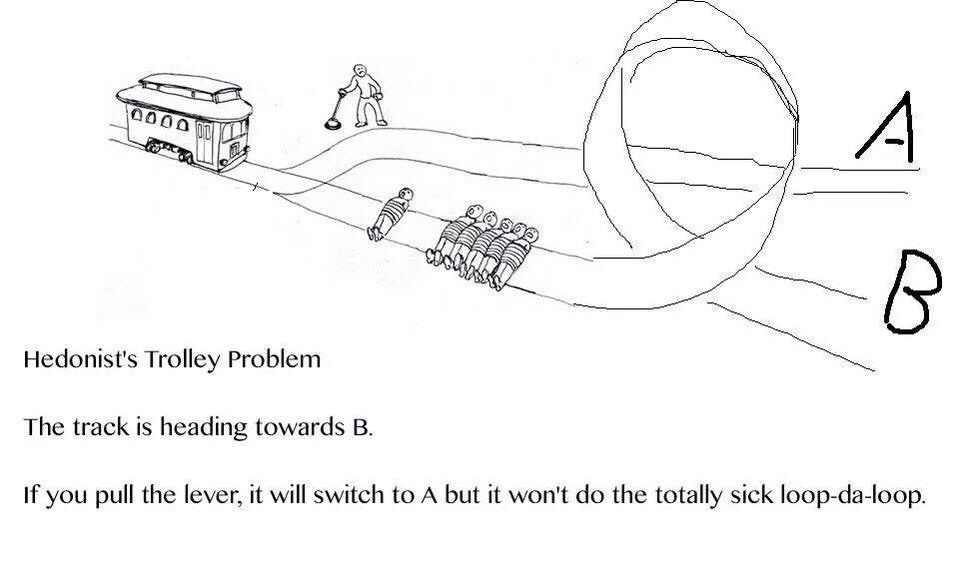

- What are thought experiments: Thought experiments are to philosophy as visual aids/examples are to instruction manuals. They are not needed, but when you can connect the instructions to the actual objects you’re working with, everything becomes easier.

I’m sure this is somewhat silly but when someone presses me on what philosophy is, I’m telling them it’s pretty much writing instruction manuals for confusing stuff.