So you want to publish philosophy? Follow the three Rs!

1. Rhetoric

No matter how good your results are or how technically sophisticated your argumentation, if it is done in an obscure way, your paper will not be published. There are at least two, but more usually three or more people that will read your paper when it is sent to a journal. First is the head editor and/or section editor. If they can’t make heads or tails of your work → Desk Rejection. If they can’t think of any external referees to send it to → Desk Rejection.

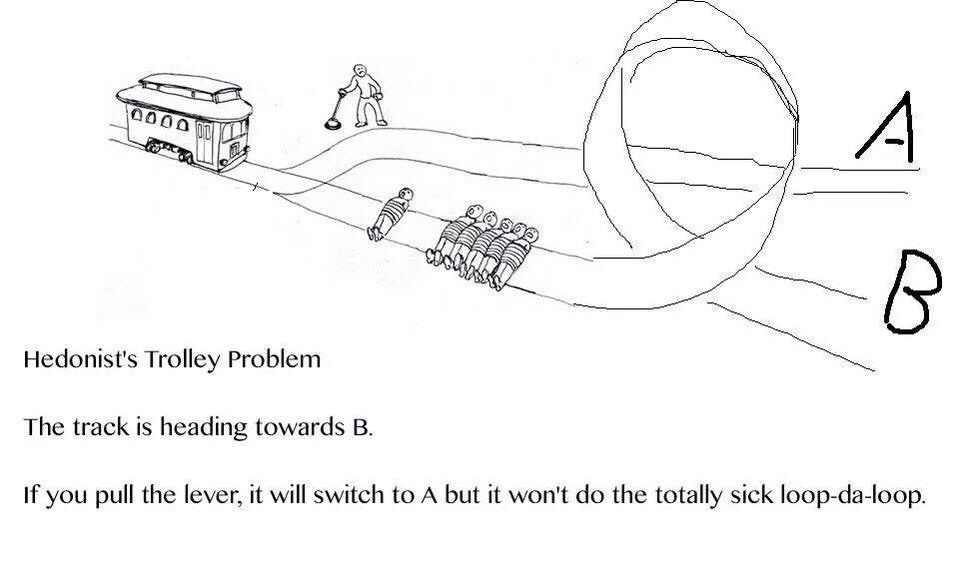

Then come the external referees. Assume they are drunk/ in an altered state of mind when they first read your paper. If it doesn’t make even a little sense to them in such a state → Rejection after 2+ months, with generic, low effort comments about your paper. Assuming it gets past this first check, and they actually sit down and read it, then it has to be something that they like.

So think about why anyone other than you should like your paper. Will it be a useful pedagogical tool for teaching a subject or idea? Does it provide fodder for or against some canonical position? Will they want to talk about it with their philosophy friends & colleagues? Is it entertaining? Are the examples clever? Does the writing flow or is it a tough slog? Are the arguments easy to spot and comprehend?

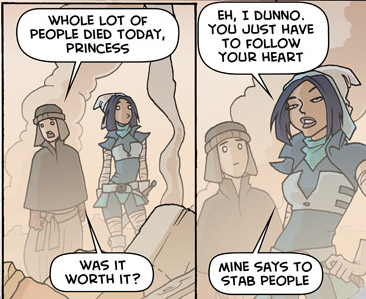

These are very important when you consider that the reviewer has to argue for your paper to the editor. Don’t make them think about why your paper has merit or relevance; it is not their responsibility to have vision or eloquence. Give them a catch-line they can use to express your contribution (see gRavitas below).

The reviewers are human, and are subject to these everyday concerns as anyone else. If your paper is rhetorically weak, they will put off reading and reviewing your painful writing. Eventually they’ll get a nag email from the Head Editor at the journal asking where their review is, which will make them grumpy and dislike you → Rejection after 4+ months, with inane things said about your paper in their comments.

2. Rigor

Academic philosophy fetishizes rigor, and hence if your work is not rigorous → Rejection, with insulting things said about your paper in the reviewer comments.

What is important here is to understand how you are getting to your conclusion. While this sounds straight-forward, it becomes muddled quickly. As the author, you become wrapped up in the research and writing, seeing connections within the work that your reader will not. Conclusions, then, that for you obviously follow from the premises will appear disconnected and un-argued-for for your reader.

Combating this requires a dispassionate look at your premises, conclusions, and how the paper gets from the former to the latter. It is the method of argumentation that is key. For instance, if arguing by cases, you need to be able to go through the cases and show that they are all the cases. If making a historical claim about what some dead person said, you need to show different possible interpretations — though not necessarily all interpretations — and why your interpretation is at least a plausible, charitable reading among those others. Logical conclusions require explicitly following the rules of that particular logic. And so on. Each method of at arriving at a conclusion has its own standards that must be carefully followed.

Also remember to do a gut-check: is this the right sort of rigorous argument for my conclusions? Don’t use a logical argument if your conclusion is historical, don’t argue by cases if it is a question of interpretation, etc. Else → Rejection, with obvious confusion about the point of your paper in the reviewer comments.

3. gRavitas

If you are still reading this, then chances are you think your work has philosophical merit. Philosophical gravitas is easy to say, very hard to do.

Basically this comes down to showing your results matter to a philosophical tradition or have real world application. Having the weight to move a tradition or moving actual living people to act is no small task, however, academics understand this. What they are minimally looking for is for your work to hook into bigger philosophical ideas or movements. Then at least, if you had anything to say, your work will be carried along with the overall wave of that tradition, and maybe give it a little boost.

Another way to think about this, tying in with rhetoric above, is that philosophy moves via people in conversation with each other and/or the tradition. So a work needs to give the reviewer, someone in the tradition, something that they think will cause conversation within that community. Again, minimally, it is understood that even providing just a few minutes of good conversation on a philosophical topic is hard, but that is all that is often needed.

Without being tied into some tradition or movement, or with no way to discuss the ramifications, your work will be seen in isolation, off on an island. Taken by itself, your paper has no ability to affect anything, and is impotent and pointless → Rejection, quickly, with generic, disinterested comments, sometimes reflecting the reviewer being insulted at having their time wasted.

.

Good Luck!