Gloria Origgi writes:

This is an application of the theory of kakonomics, that is, the study of the rational preferences for lower-quality or mediocre outcomes, to the apparently weird results of Italian elections. The apparent irrationality of 30% of the electorate who decided to vote for Berlusconi again is explained as a perfectly rational strategy of maintaining a system of mediocre exchanges in which politicians don’t do what they have promised to do and citizens don’t pay the taxes and everybody is satisfied by the exchange. A mediocre government makes easier for mediocre citizens to do less than what they should do without feeling any breach of trust.

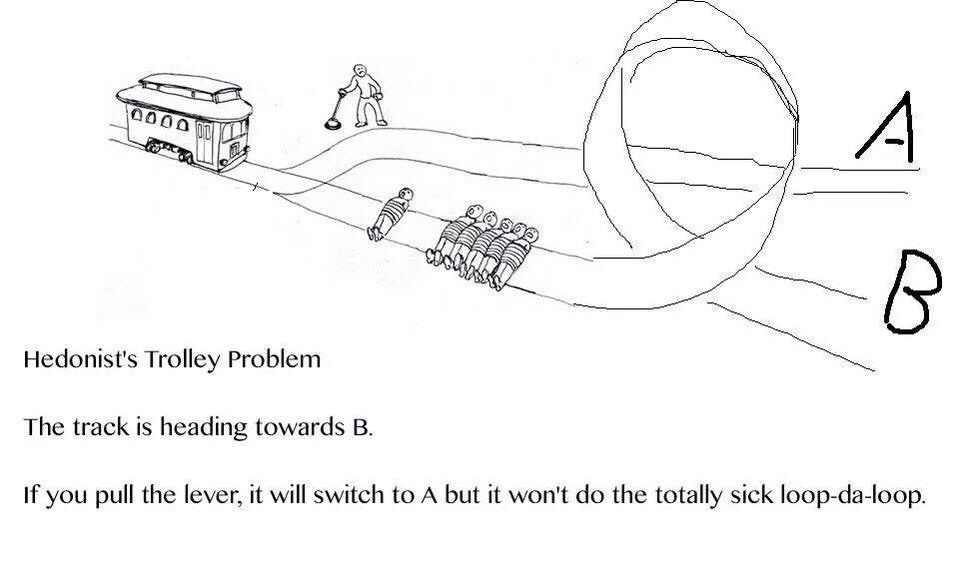

She argues that if you elect a crappy politician, then there is little chance of progress, which seems like a bad thing. People do this, though, because maintaining low political standards allows people to have low civic standards: if the politicians are corrupt, there is no reason to pay taxes. Likewise, the politicians who have been elected on the basis of being bad leaders have no incentive to go after tax cheats, the people who put them in office. Hence there is often a self-serving and self-maintaining aspect to making less than optimal decisions: by mutually selecting for low expectations, then everyone cooperates in forgiving bad behavior.

This account assumes that bad behavior of some sort is to be expected. If someone all of a sudden starts doing the ‘right thing’ it will be a breach of trust and violating the social norm. There would be a disincentive to repeat such a transaction again, because it challenges the stability of the assumed low quality interaction and implied forgiveness associated with it.

I like Origgi’s account of kakonomics, but I think there is something missing. The claim that localized ‘good interactions’ could threaten the status quo of bad behavior seems excessive. Criticizing someone who makes everyone else look bad does happen, but this only goes to show that the ‘right’ way of doing things is highly successful. It is the exception that proves the rule: only the people in power — those that can afford to misbehave — really benefit from maintaining the low status quo. Hence the public in general should not be as accepting of a low status quo as a social norm, though I am sure some do for exactly the reasons she stated.

This got me thinking that maybe there was another force at work here that would support a low status quo. When changing from one regime to another, it is not a simple switch from one set of outcomes to the other. There can be transitional instability, especially when dealing with governments, politics, economics, military, etc. If the transition between regimes is highly unstable (more so if things weren’t that stable to begin with) then there would be a disincentive to change: people won’t want to lose what they have, even if it is not optimal. Therefore risk associated with change can cause hyperbolic discounting of future returns, and make people prefer the status quo.

Adding high risk with the benefits of low standards could make a formidable combination. If there is a robust black market that pervades most of the society and an almost certain civil unrest given political change (throw in a heavy-handed police force, just for good measure), this could be strong incentive to not challenge an incumbent government.