“You’re being unreasonable!”

One or more of you may have had this directed at you. But what does the speaker mean by it?

Presumably the speaker believes that the listener is not acting according to some given standard. However, if the speaker had an argument to that effect, the speaker should’ve presented it. Hence, all the above statement means is that the speaker has run out of arguments and has resorted to name-calling: being unreasonable is another way of saying crazy.

Now, though, the situation has reversed itself. It is not the listener that has acted unreasonably, but the speaker. Without an argument that concludes that the listener is being unreasonable, then it is not the listener that is being unreasonable, but the speaker. The speaker is name-calling, when, by the speaker’s own standards, an argument is required. For what else is reasonable but to present an argument? So, by saying that the listener is being unreasonable, in essence the speaker is declaring themself unreasonable.

But, yet again, the situation reverses itself. If a person has run out of arguments, and makes a statement to that effect, then he or she is being perfectly reasonable. This returns us to the beginning! Therefore, by making a claim about someone else being unreasonable, you paradoxically show that you yourself are and are not reasonable, such that if you are, then you are not, and if you are not, then you are.

I don’t understand how the last paragraph of your post connects to the earlier ones about not presenting an argument for the claim of unreasonableness. “If a person has run out of arguments, and makes a statement to that effect, then he or she is being perfectly reasonable.” So if I run out of arguments, and I say to my listener: “I’ve run out of arguments”, I’m saying that my listener is unreasonable? I don’t get it.

Also, I don’t see how “Without an argument that concludes that the listener is being unreasonable, then it is not the listener that is being unreasonable, but the speaker.” is true, since the listener may be unreasonable even without the speaker presenting an argument that the listener is unreasonable.

so you are saying that a person cannot be unreasonable (because I cannot reasonably say the true statement that a person is unreasonable).

But does this not mean that every person is always reasonable?

Insofar as a contradiction is created by calling someone unreasonable, and anything follows from a contradiction, then, yes, every person is always reasonable. But by the same light, up is down, left is right and anything else you want.

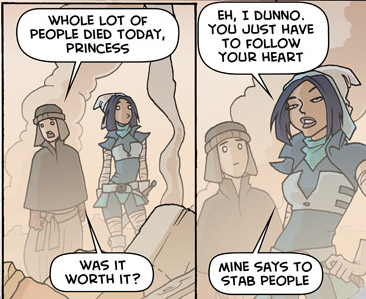

On the other hand, if you do not call anyone unreasonable, then there is no problem: if you don’t contradict yourself, then the conclusion that every person is always reasonable does not follow. So if you want to avoid the paradox, just don’t call anyone unreasonable. Call them stupid or pig-headed or whatever else is your favorite insult at the time.

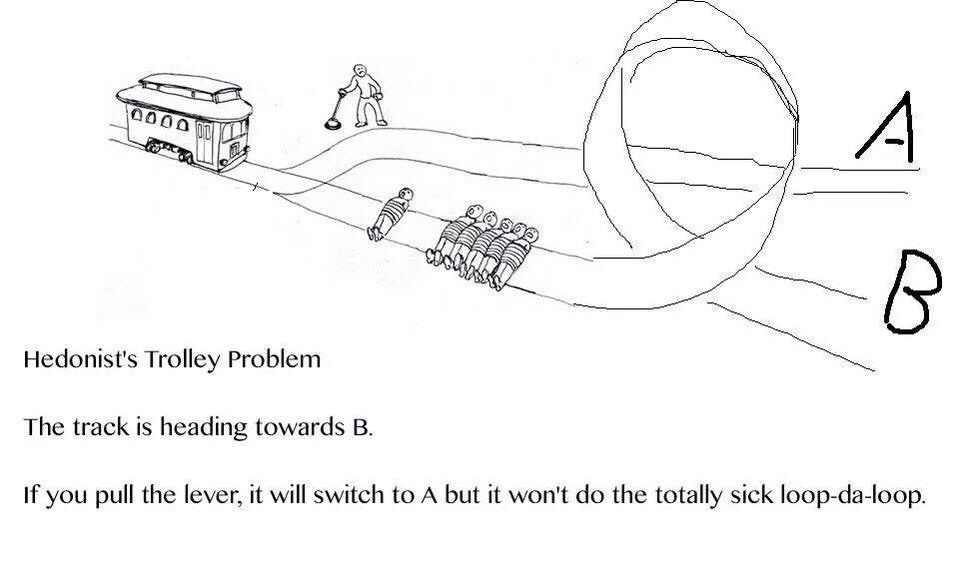

I think the real problem here is that we put an awful lot of uncritical faith in reason. This paradox points out that the foundations of our modernist/ enlightenment-based belief in reason are not so sturdy. If anything, it indicates we need to be a bit more careful about what we think we are up to when we argue.

>> So if you want to avoid the paradox, just don’t call anyone unreasonable.

But this is very weird: a person can have property u but if you actually say that a person has property u then you create a contradiction…

I apologize wolfgang- I was editing my response first comment while you responded. Thankfully it doesn’t look like any (or too much) harm was done to your response.

Yes. It is weird. And if you can come up with a solution, I’d love to hear it.

anonimal-

“So if I run out of arguments, and I say to my listener: “I’ve run out of arguments”, I’m saying that my listener is unreasonable? I don’t get it.”

No, if you run out of arguments and tell your listener that you have, then you are being reasonable for saying that you have no more arguments. But if you are being reasonable, then what you said initially should be taken seriously, and what was said was that your listener is unreasonable. This is what reverses the situation.

I’m also assuming that in a rational discussion each side presents its arguments, and that this is the reasonable thing to do.

To your last question (and wolfgang’s second comment): the paradox is generated by calling someone unreasonable and makes no specific claim (without more arguments) about whether the listener is crazy or not according to some other argument. Which may be a little weird, but such are paradoxes in general.

hmm. Maybe I should call this the Rationality Paradox- ‘irrationality’ works just as well as ‘unreasonability’ and rationality may have more rhetorical force.

a version of Russell’s paradox.

For some claims, it would be unreasonable to provide reasons that they are true.

More seriously, I am unconvinced that if I make the assertion “S is unreasonable,” then there is an implication that I have run out of arguments. Perhaps I think the reasons too obvious to state. Perhaps I think they would be a waste of time to state. Perhaps I am waiting to see whether my interlocutor will re-consider without my having to state the reasons that I have for thinking him or her unreasonable. …

But without the implicature that I have run out of reasons, the contradiction does not obtain. Hence, it is not paradoxical to say that someone is unreasonable.

Jonathan- Sure, if you using ‘unreasonable’ to mean something other than what I mean, then the paradox does not hold. But if you have all these other things to say, which you claim ‘being unreasonable’ stands in for, then you ought to just say what you mean. Calling someone unreasonable is rather insulting: it is like trying to call someone crazy in a nice way, as if it there was a nice way to call someone insane. So, in the case I mention, where you do actually mean what you say, ie the listener is unreasonable, the paradox holds.

Hi French! You are right that this has a connection to Russell: since everyone considers themself reasonable, we are in a self-membership situation. However, this is unique in the way the problem arises: the ascription of unreasonability to someone else implies something about the reasonability of the speaker. This happens (I think) because of an underlying assumption of what reason is, as I mentioned above, likely stemming from a modernist view that puts a lot of stock in human rationality. So unlike Russell’s Paradox, which sank Frege’s Logicism by showing it put too much stock in logic alone, this paradox is not directed at a mathematical or logical framework, but a conception about rationality itself.

“So, in the case I mention, where you do actually mean what you say, ie the listener is unreasonable, the paradox holds.”

I’m pretty sure that is not true. One might have reasons for thinking that one’s interlocutor is unreasonable. But the unreasonableness of the interlocutor might not be *entailed* by the evidence. If the claim of unreasonableness is made likely (but not strictly entailed) by the evidence, then saying, “You are (being) unreasonable,” is both informative and backed by reasons. (I will not stop to reflect on the potential problems of equating “You’re being unreasonable” with “You’re unreasonable.”) One might offer all of the evidence and yet the interlocutor might not see the connection to his or her unreasonableness.

A: You’re being unreasonable.

B: What do you mean?

A: You’ve just bet me 2:1 that this coin will come up heads.

B: And?

A: Well, you’ve also just told me that you think the coin is fair.

B: So?

A: By your own lights, you are likely to lose money!

B: Ooooohhhhhh.

If the interlocutor *is* unreasonable, a failure to reason properly about the evidence for his or her unreasonableness might even be likely. Maybe rather than ending in the “Oh” of dawning comprehension, the conversation ends in the “So what?” of defiant ignorance.

Also, there is a dialectic issue.

If A and B have a conversation in which B says or does many things that strike A as unreasonable. The dialogue then goes as follows:

A: You’re being unreasonable.

B: Why would you say that?

A: Well, you said x, y, z, …, and all of those things are unreasonable things to say.

B: So what?

A: Well, people who are being unreasonable often say unreasonable things, so it seems like a good hypothesis that you are being unreasonable.

B: I don’t get it.

You might try to push on A’s judgment that this or that claim is unreasonable, but I don’t think those judgments lead to your paradox. And besides, A might have good reasons that he or she could give if pressed. This is just the way dialogue goes. We make assertions, expecting to find our interlocutors agree with us. When pressed by disagreement, we offer reasons for our assertions (provided we have any).

Your “paradox” depends crucially on two claims:

(1) If one has an argument to the effect that p is the case, then one should offer the argument rather than simply asserting that p is the case.

(2) When one says, “You are being unreasonable,” one effectively admits that one has run out of arguments and is now resorting to name-calling.

But neither of these claims is true. With respect to the first claim, I rejoin: If one believes that p is true one should begin by simply asserting that p. If one’s interlocutor agrees, then all is well. No reasons need to be given in that case. It is only when the interlocutor disagrees that reasons need to be called up in an effort to settle the disagreement. Your requirement would make actual dialogue difficult if not impossible; therefore, it is an unreasonable requirement.

With respect to the second claim, I rejoin: In many cases, pointing out to one’s interlocutor that he or she is being unreasonable actually leads to agreement without further reason-giving! Suppose I have asked my wife to do me a favor that requires a large commitment of her free time. She agrees to do the favor for me. Later, I complain that she is not spending enough time relaxing with me. She tells me that I am being unreasonable. Her assertion leads me to reflect on my demands, and I see that she is right: I *was* being unreasonable. No doubt she had reasons for her claim that I was being unreasonable. But she did not need to actually articulate them. All she needed to do was get me to reflect on my commitments. In fact, requiring that she actually give her reasons would (in many cases) be an unreasonable demand.

I still don’t get it. Maybe this has to do with the two claims Jonathan Livengood presents as crucial to the paradox, but I don’t even get the basic idea even with those claims granted.

Saying “You’re being unreasonable!” without being willing to present an argument for that if asked for it, is being unreasonable (at least in a seminar room discussion). That’s as far as I’d go. But that isn’t necessarily the case when saying “You’re being unreasonable!”.

Re: nogre May 1, 2012 at 12:37 pm: “No, if you run out of arguments and tell your listener that you have, then you are being reasonable for saying that you have no more arguments. But if you are being reasonable, then what you said initially should be taken seriously, and what was said was that your listener is unreasonable. This is what reverses the situation.”

So let’s suppose one first says: “You’re being unreasonable!” without being willing to present an argument for that claim. Then one’s being unreasonable. Subsequently making a statement to the effect that one’s run out of arguments doesn’t change one’s being unreasonable in the statement before that. At most one could say that the statement to the effect that one’s run out of arguments is reasonable, and that the name-calling is unreasonable.

JL- I really like the example with your wife. In that case, she has a deep prior understanding of what you would consider rational. With this prior understanding of your rationality, she knows that all she needs to do is to give a hint about something you did that would fail by your own standards. So she is using ‘unreasonable’ as a shorthand for an argument that she does not need to make because she knows you will make it for her. I agree that your wife is 100% rational when she acts in this way.

I happily admit I hadn’t had this example in mind above. I was thinking more along the lines where there was no prior deep understanding of how the other person thinks, which likely happens much more often when in a disagreement with someone.

In this more likely situation that I was considering, to assume people always have another argument that they are not presenting when they call someone unreasonable begs the question against my argument. I haven’t used my words in any unusual way or pointed out a very unusual situation: everything I described is common enough. And I see no a priori reason to hold that people always have further arguments. So condition 2 holds.

As for the first claim, I already admitted that if you are using ‘unreasonable’ as a shorthand for something else, then the paradox doesn’t hold. But, again, I haven’t mentioned some unusual situation, so in the situation I indicated, the paradox does exist.

Anonimal- It looks like you are pointing out that there are other specific times/ situations when the paradox fails. I agree, as with JL’s wife example, that there are times when the paradox does not hold. However, I don’t see this as a problem: all paradoxes hold under certain conditions and contexts, and do not exist otherwise, eg Russell’s Paradox holds when Frege’s law V is in effect, and does not otherwise. As I haven’t identified any unusual situation in generating the paradox, it holds under those normal conditions as I have mentioned and it doesn’t matter to me if it does not hold otherwise.

To your second point: I claimed that calling someone unreasonable is an admission that the speaker had run out of arguments, as well as insulted the listener. I’ll grant that if you separate out the statement about having no more arguments and the insult, then we’ll end up as you said with being reasonable at one point and then not reasonable later. But, again, my initial situation is a common enough everyday sort of thing. I’ve been accused of being unreasonable after I shredded someone’s arguments and they didn’t like it. So the paradox holds in the situations I’ve described.

Re: nogre said, May 1, 2012 at 12:37 pm: “No, if you run out of arguments and tell your listener that you have, then you are being reasonable for saying that you have no more arguments. But if you are being reasonable, then what you said initially should be taken seriously, and what was said was that your listener is unreasonable.”

I think I understand why I don’t get why there’s a paradox: apparently “being unreasonable” here implies that everything one says shouldn’t be taken seriously (shouldn’t be taken as “reasonable”), because “if you are being reasonable, then what you said initially should be taken seriously” and by your standard, apparently, one’s already “being reasonable” by making one reasonable statement (“I’ve run out of arguments”), even if the previous statement (““You’re being unreasonable!”) is unreasonable. But I don’t see how that’s true, the assumption that being unreasonable implies that all one’s statements aren’t to be taken as “reasonable”.

re: apparently “being unreasonable” here implies that everything one says…

I don’t think I need the universal ‘everything’ to make my point. I only need the statement made — at that time — to be subject to being reasonable or not. So the paradox is localized, sure, but I don’t need to make the stronger claim about everything a person says: I only need it to be self-referential.

I also operate under the principle of charity, which means I try to understand people as making rational interesting points (in order to be fair to other people’s point of view, to get the most out of discussion, etc.). So I do assume people are being rational, at least to begin with. I assume you operate similarly, but I can see how small changes in this assumption can lead to significantly different views. So something along these lines may be at work here, and I don’t know if they are resolvable since charitability is inherently an assumed outlook.