What comprises an ethical decision according to theory?

For the Consequentialist the crux is always in determining and executing the best consequences.* This means that making a consequentialist decision involves two steps. First is to imagine different possible futures and evaluate them. Once the evaluation is done, the consequentialist chooses the future scenario that maximizes the ‘Good’ (or what have you) and works towards realizing that scenario. Being moral is having skill in figuring out the best future and achieving that future.

The task in Deontology is to obey rules and imperatives. To follow a rule is to understand the rule, when it applies, and how you should act to be in accordance with it. Being moral is understanding imperatives and comporting yourself to act according to them.

In Virtue Ethics the goal is to be virtuous. We become virtuous by habit: by habituating ourselves in certain ways we change ourselves into the person we wish to become. Being moral is having undertaken the work to become the person we wished to be. Once we are the virtuous person we wish to be, whatever we decide to do is the moral thing.

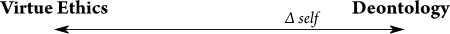

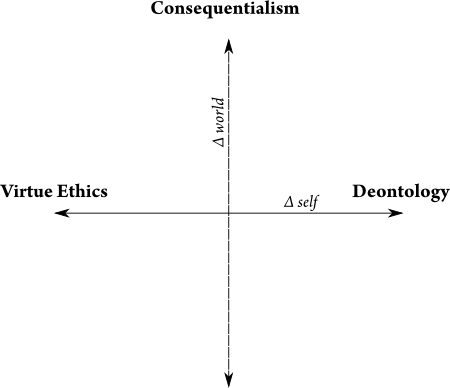

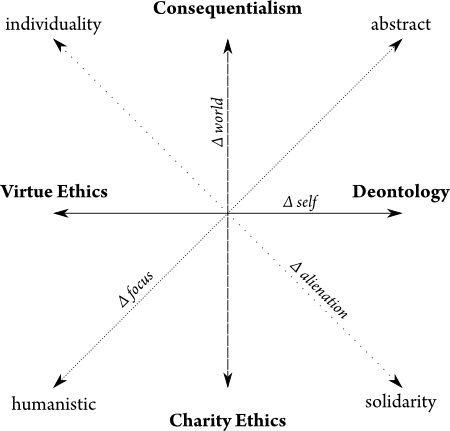

From this short sketch we can set up some interesting oppositions. The first thing to notice is that both Deontology and Virtue Ethics are concerned with how an agent has changed themself in order to act morally. A virtuous person has habituated themself according to their idea of excellence and a deontologist has comported themself to act according to the rules. Though the target of the change is different, the act of self-change is common to both theories.

|

A consequentialist, however, is less concerned with changing themself and more interested in how they can effectively change the world. It doesn’t really matter to the consequentialist how the best scenario is achieved, so self-improvement is less important than world-change.

|

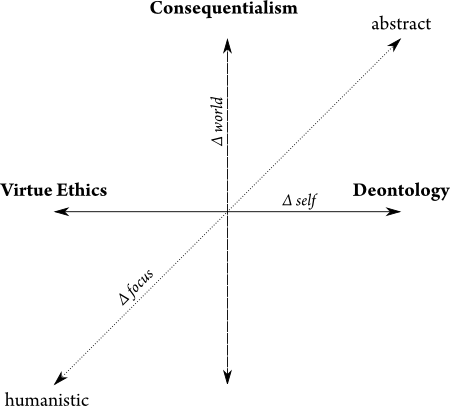

Consequentialism and deontology have something in common that virtue ethics does not. The two modern ethical systems both have an abstract standard for deciding what is moral. Consequentialists have a calculation of the good and deontologists have rule systems to obey. Both calculating the good and following a rule system can be thought of as an objective, independently evaluable procedure. Living the life you want to lead according to your virtues, does not require following an independent abstract procedure. It is, instead, based upon an understanding of human life.

|

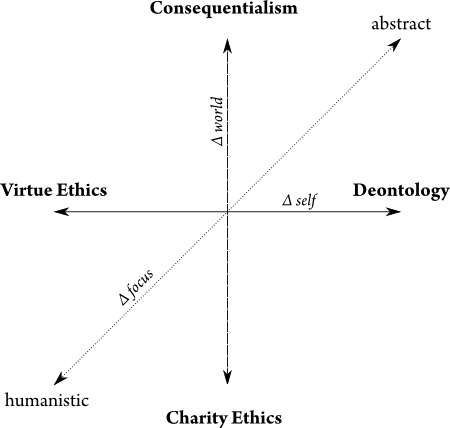

As you can see by the way I have set up the opposition, I left a space at the bottom for an ethics in which is similar to consequentialism in that it looks to change the world, and similar to virtue ethics in that it is humanistic. Very recently I have been working on something I call Charity Ethics, and I believe it fills out the opposition nicely:

|

Charity Ethics is based upon increasing our empathy for others. To increase our empathy we have to act charitably towards each other; only by acting charitably do we have the opportunity to find common ground. So the fundamental decision of charity ethics is how to be more charitable so that we can find more common ground and hence become more empathic.

Like consequentialism the thing that needs to be changed is the world: we have to practice charity and find new ways to be charitable. Although the end goal of this practice is to become more empathic, this is not part of the ethical decision procedure- it is a consequence.

Charity Ethics is also humanistic like Virtue Ethics. Instead of using an abstract standard, each person must find ways to engage charitably with other people (and other organisms, potentially). It is through this charitable engagement with others that ethical decisions can be made and evaluated.

Lastly consider the remaining dimension, from the upper left to bottom right, which is a property that Virtue Ethics and Consequentialism agree on but oppose both Deontology and Charity Ethics. Perhaps there are other properties, but I lighted upon what I call ‘alienation.’ Alienation is how the ethics prioritizes individuals and groups.

|

Both consequentialism and virtue ethics are very accepting of an individualistic perspective. Under consequentialism a person is to maximize of the ‘good,’ which takes no account of personal, family or other social relations. An agent decides the best possible abstract outcome and acts accordingly. Likewise, virtue ethics is focused upon living an excellent life, which may mean different things for different people. How to live excellently is a personal decision and, hence, may not include personal, family or social relations.

Opposing this individualism is solidarity. A deontologist will likely take personal, family and social relations into account as part of their obligations. A parent will have an obligation to their child over the well-being of other children. Similarly Charity Ethics requires other individuals, else there would be no one to be charitable with. Moreover, since a person will have greater opportunity to help a child or friend, or close social group, these personal relations can be prioritized.

This opposition cross is based upon the ethical decision making under different theories. The similarity between Virtue Ethics and Deontology, with regard to how both seek to change the self, while Consequentialism is based on changing the world, is something I had never before considered. It might be a trivial issue, but, since it came directly from the question about making ethical decisions, it seems more significant. Also, Charity Ethics being a humanistic ethical theory that focuses on changing the world is nice both in the sense that it is new and different, and also that it fills out the chart in direct opposition to Consequentialism. The value of the chart will ultimately depend on the significance of initial question, but, even if we disregard it, this diagrammatic approach still provides some interesting ways to analyze the ethical theories.

————————————

Just a thought… Maybe it’s possible to formalise this in terms of the origin/destination of normativity.

Individual -> Individual = Virtue

Individual -> Group = consequentialism

Group -> Individual = deontology

Group -> Group = charity

Then “abstractness” appears to be correlated with hetero-normativity, while “humanity” is correlated with auto-normativity.

Hi quen_tin,

That’s an interesting way to break it down. I hadn’t considered normativity on its own when constructing the opposition, but I think your analysis is correct.

Does it matter that your ‘self’ is also part of the ‘world’? All consequentialist theories allow a person to include themselves as part of the world that is to be changed. The opposition between these two variables seems somewhat forced. The alleged focus on ‘self’ seems equally strange in the case of deontology: the good agent, for such theorists, is characteristically focused on others, and on the ethical demands made by those others.

Second: as I understand it, few modern consequentialist theories are direct, which means that most actually do not reccommend the decision-procedure you describe here. The common distinction between decision-procedure and right-making features of actions may cut across many of your distinctions, here.

Hi N,

Thanks for the comment. I think it matters that the ‘self’ is part of the world for consequentialists, but, this actually is part of the point: the self has to be treated as part of the world, it is not primary. Likewise the deontologist starts with the ‘good agent’ and then moves on to others. The question here is how we make ethical decisions, how we start to decided, and this kinda flips things around.

I’ll grant that modern theories are highly sophisticated and that my account wasn’t more than a quick gloss. But if consequentialists are not looking at consequences, deontologists aren’t following rules and virtue ethics people aren’t doing whatever it is that their virtues say, then we’ve lost the distinctions anyway.

Unfortunately, I think the suggestion is a non-starter, since consequentialists have long taken pains to point out that their principles do not imply that behaving rightly requires figuring out in advance what action would maximize the good, and even that their principles actually entail that doing so is often wrong.

Hi Puffy (sorry)

You may be right that my gloss of consequentialism is a straw man. It was not meant to be a complete description.

However, as long as we are still talking about a consequences-based system, this makes the consequences a fundamental part of the decision procedure. Since the decision procedure is what is at stake here, it still seems that my points make sense in reference to this, even if I am using a very naive version of the theory.

The SEP entry on Consequentialism has a nice section on consequentialists who do use it as a decision procedure and those who don’t. Those who don’t should not be included in what I said above, though it also remains to be seen on what basis they do make ethical choices.