Here is a selection three reviewers’ comments from two well-ranked journals about a paper of mine:

- “Be that as it may, there really isn’t a recognizable philosophical project here that would merit consideration by [Misspelled Journal Name].”

- “I do not see how the author can improve the paper, since its motivation is ungrounded.”

- “This paper makes interesting, important claims and it should with improvements appeal to a broad and diverse audience.”

It would be one thing if all reviews were like 1 and 2. I’d be some mix of crazy, mistaken and uninformed. The issue is review 3. That reviewer saw my work completely differently than the others, basically exactly as I was hoping it would be understood.

How can the disparity in views be explained?

One way could be to blame ‘cartels’ of academics. The idea behind academic cartels is that reviewers belong to some school of thought, a cartel. They, consciously or not, favor work that supports their cartel by referencing them or providing more arguments in their support. By supporting ‘their’ work and rejecting others’, they increase the relative importance of themselves and their friends in academic standing.

Under the the cartel theory, reviewers 1 and 2 rejected my paper more because my ‘philosophical project’ did not support them and their projects, than me not having a project or some actual problem. This view is backed by the fact that reviews 1 and 2 had almost no engagement with any specific claims or arguments in my paper, but instead made critical generalizations about what was said or how it was said. For instance, reviewer 1 said I relied too heavily on Prominent Philosopher X and reviewer 2 said I had not read enough of same Prominent Philosopher X. The criticisms are basically meaningless since they could mean any number of things — no details of what I had wrong were given — and I could take them to just be a smokescreen for their bias.

I’m sure some of this is going on, but I don’t think cartel bias is the main issue. More likely is overwork. It is just easier to make up a BS criticism than an actual criticism. Again, consider the criticism having to do with Prominent Philosopher X: the underlying issue is that they both criticised without ever mentioning what exactly I had said wrong. Moreover, a journal editor would have a tough time arguing with this sort of accusation. I think the reviewers were more concerned with having something defensible to say than saying anything substantive.

Said differently, journal referees are highly risk averse. There is no incentive for them to get themselves into a position that requires more work. They already put in extra time to be the referee, so making difficult arguments is overmatched by making defensible, if nonsensical, arguments.

There are two approaches to this problem: top down from the journals and bottom up for the paper writers. Journals can institute policies that incentivize better reviews. A review of reviews, if you will. A new journal that only accepts reviews of other papers could be formed. This meta-journal would highlight the best and the worst, showing what good reviews and (anonymous) poor reviews are. This would help value service to the community as a reviewer, have pedagogical use in showing best practices and wouldn’t make people avoid being reviewers.

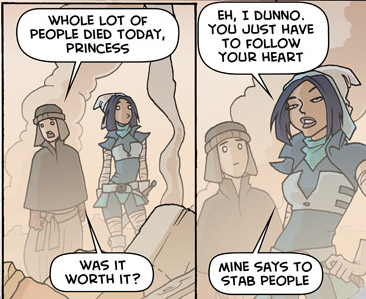

As a writer I advocate figuring out the best rhetoric such that the poor overworked reviewer will think they are getting what they want. Then, if they really don’t like the paper, they will have to come up with a more substantive criticism. Rhetoric, rhetoric, rhetoric: the arguments and conculsions will be the same, but how they are dressed up will be different. I think some philosophers believe themselves to be above ‘mere’ rhetoric, but from everything I’ve seen, this belief just serves to cover up how much we are affected by it. We drink our own Cool-Aid all too often, and a smart writer should use this to their advantage.

Apt & clear!